Big Food Disinformation: Four Industry Strategies Science Journalists Should Understand

Photo: evelynlo / Pixabay.com

SAN FRANCISCO—Knowing an opponent’s movements can give players an advantage in the game. That saying is especially apt for science journalists who cover the public and media manipulations from giant food and beverage corporations.

On 29 October at the World Conference of Science Journalists 2017, experts shared key ways to identify the disinformation strategies used by “Big Food” industries to minimize negative perceptions and block regulations. Speakers in a panel titled “Leveling the Playing Fields: Science Journalism and Big Food” described their work in this arena in South Africa, Mexico, India and the United States.

Soft drink companies in Latin America boldly stated there is “no relation between soda consumption and obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases."

Panelists focused on arguments put forward by the industry against the proposition of increasing the price of soft drinks. These positions were similar to those from the tobacco “playbook” decades ago, in which the industry denied a link between smoking cigarettes and lung cancer.

For instance, soft drink companies in Latin America boldly stated there is “no relation between soda consumption and obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. It is only about energy balance,” said Alejandro Calvillo Unna, director of the consumer rights organization El Poder del Consumidor.

According to the panelists, being aware of the following four tactics used by Big Food companies and their publicity machines will help journalists report responsibly on the industry and its public health impacts:

Industry tactic #1: “Attacking us will cause economic problems”

This approach was shared by former health journalist Shalini Anand, communications manager of the Centre for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in New Delhi, India. By claiming that their industry creates jobs and promotes “corporate social responsibility” in developing countries, Anand said, Big Food companies seek political support, strive for social respectability, and threaten to fire employees.

In South Africa, “children under the age of two are more likely to drink a fizzy drink than milk, and one in ten schoolkids is obese,” said Kerry Cullinan, managing editor of Health-e News Service, an independent non-profit news agency. The economic argument put forward by industry is accepted and promoted by “mostly business journalists,” said Cullinan. These journalists, she said, “condemned soda taxes for their impact on the economy in the short-term.”

Panelists recommended that reporters analyse the long-term consequences of economic and social impacts, placing the problem in the proper societal context.

Industry tactic #2: Create “reasonable” doubts about scientific research

When conclusions from independent researchers are not positive about corporate practices or products, big business tries to create uncertainties. For example, the Beverage Association of South Africa affirmed that there is “no scientific basis on which to claim that sugar is an unhealthy food.” Indian companies claimed that “sugar does not cause harm; it’s fat.”

Moreover, industries often refer to scientific studies but misrepresent the original papers. They even commission biased studies that are published in journals lacking peer review, said Calvillo.

Panelists advised that reporters always try to answer these questions about industry-funded studies: Where was the research published? Who funded the investigation? Why do the researchers trust the results?

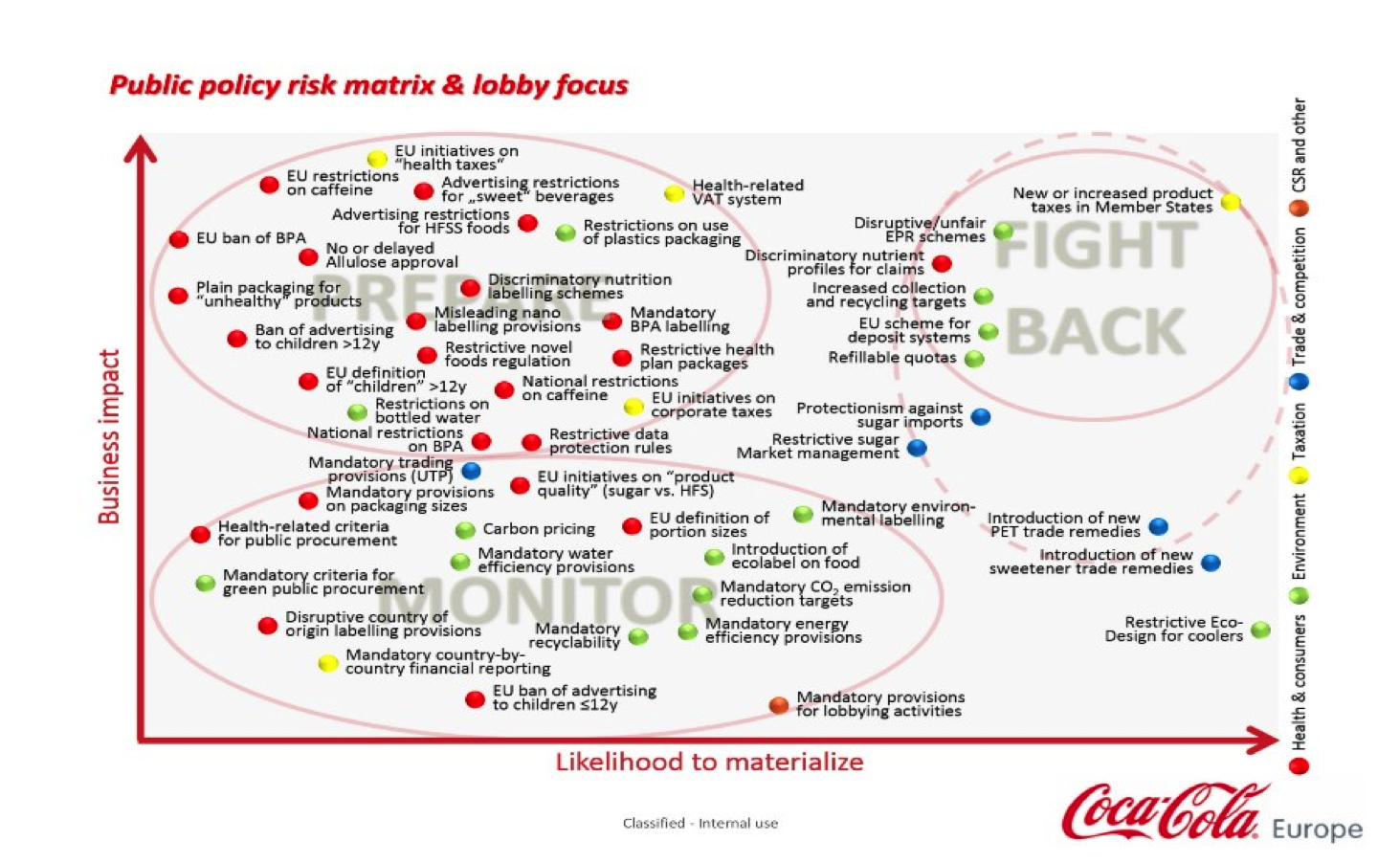

An internal chart from Coca-Cola Europe reveals how the Big Food industry tracks potential public and legal challenges and prepares to counteract them. Graphic courtesy of Alejandro Calvillo Unna/El Poder del Consumidor.

Industry tactic #3: Use attractive advertising campaigns

Consumers have access to more information than ever before, but it is also easier for each consumer to get just a narrow range of information. The power of social media represents an opportunity for big companies to generate targeted narratives that attract consumers, especially the youngest ones. For instance, said Anand, “Sweets are big part of Indian culture, but there’s been a shift from traditional sweets to processed sugar” because of such messages.

“The companies come in and sell us a lifestyle that we don’t need and that isn’t good for us,” said Cullinan. The beverage industry in South Africa spends about $28 million per year on advertising, she said; the country’s Department of Health has a promotion budget of $155,000.

Journalists should try to promote transparency and public vigilance on campaigns that undermine scientific evidence, the panelists said.

Industry tactic #4: Water down social policies

Another common Big Food practice is creating associations and front groups to gain credibility and strength. For example, in Mexico, “the soda industry included the sugar cane industry and a national association of local store owners in their campaign against soda taxes,” Calvillo said.

These groups have more power to undermine science, influence public opinion, and affect social policies, the speakers said—mainly by gaining privileged access to policy makers.

In the face of these constant tactics, the panelists urged journalists to improve the quality of reporting on Big Food and give readers what they need for evidence-based decision-making. Although industry will always fight back, reliable journalism will continue to make a difference.

—

Michelle Montserrat Morelos Cabrera is a science journalist for the television program simbiosis, broadcast by TV UNAM in Mexico City, and works for the NGO Communication and Environmental Education Fund. She was an associate student to the communication unit of the Physics Institute at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and a founding member of the Mexican Network of Science Journalists.