Undersea Robots Capture the Lives of Mysterious Deep-Sea Jellies

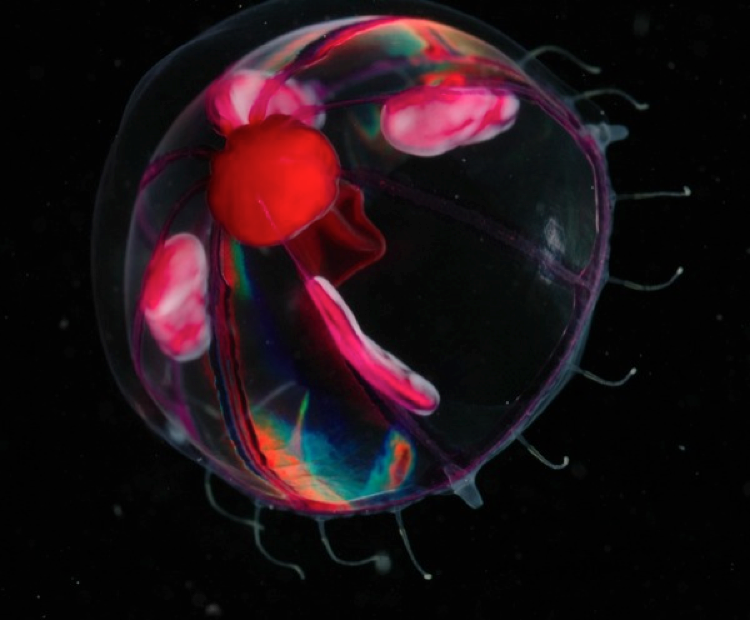

An undescribed species of hydromedusa in the genus Tetrorchis. This jelly is about 2.5 centimeters across. Photo: Steve Haddock, MBARI

MOSS LANDING, California—Forget Mars. The next frontier in the search for undiscovered life forms may lie deep in the oceans of our own planet. Thousands of meters below the ocean’s surface, hulking underwater rovers probe the remote depths looking for mysterious creatures.

“It really is like an alien landscape, but just right on Earth,” said Steven Haddock, a marine biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, or MBARI. He described this underwater world to visiting journalists on a 30 October field trip during the World Conference of Science Journalists 2017.

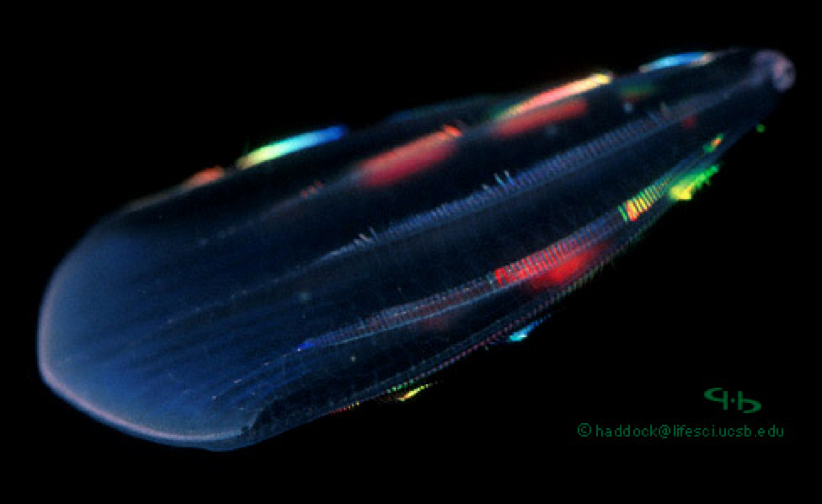

"Jellies" come in many bizarre and beautiful varieties.

Haddock studies “jellies”—the vast array of gelatinous life forms that float, swim, and pulsate through the deep sea where it’s difficult to explore.

These creatures, which come in many bizarre and beautiful varieties, evolved delicate bodies that are transparent or nearly so. Researchers usually drag nets through the water to collect sea creatures for study. But for fragile jellies, this technique is destructive. Like pushing jelly through a sieve, it reduces them to mush.

Underwater robot explorers

Instead, to find out which jellies are out there and what roles they play in ocean ecosystems, scientists at MBARI explore the deep sea with robots called remotely operated vehicles, or ROVs. The ROVs travel while tethered to a ship at the surface by a cord that can be thousands of meters long. The connection powers the ROV and transmits data back to mission scientists above in the ship’s control room.

One ROV used at MBARI is Doc Ricketts, which can explore down to 4,000 meters deep. Aside from having mechanical arms that allow researchers to pick up or place items on the sea floor, Doc Ricketts doesn’t look much like a robot. It’s big and boxy and weighs nearly 5,000 kilograms.

The remotely controlled vehicle Doc Ricketts, a deep sea-exploring robot that records the lives of many gelatinous creatures about which little is known. Photo: Carolyn M. Wilke

A commercial deep-sea robot developed for oil exploration, Doc Ricketts has been repurposed with sensors that help scientists understand the deep ocean environment. Some of its samplers suck jellies gently into bottles to bring them back to the surface.

“Everything that’s loaded has to be able to go down and withstand the crushing pressure of 4,000 meters.”

Doc Ricketts also serves as a film crew. It carries LED lights to illuminate the area in front of the ROV and high-definition cameras to catch whatever swims by. The camera lenses are made of thick glass to prevent them from shattering.

“Everything that’s loaded has to be able to go down and withstand the crushing pressure of 4,000 meters,” said Doc Ricketts chief pilot Knute Brekke. At that depth, the ROV experiences roughly 400 times the pressure that we feel at sea level from the atmosphere above us—equivalent to the weight of a car pressing down on an area the size of a postage stamp.

By using the ROVs to watch the deep sea, Haddock and other MBARI scientists have illustrated the lives of jellies, including many never seen before. In his time at MBARI, Haddock and his team have identified dozens of jelly species, many of which they are now documenting in the scientific literature.

The ctenophore Beroe forskalii, which under light appears to be fringed in rainbow colors. It’s about 13 centimeters long. Photo: Steve Haddock, MBARI

Haddock is working on piecing together the marine food webs that include jellies. The question of who’s eating whom might seem elementary, but the difficulties of exploring the deep sea mean that marine biologists have been studying these dietary patterns for decades.

Typically, researchers catch animals and look at what’s in their stomachs to figure out what they eat. But since catching fragile jellies is difficult even with the ROV, they use a different strategy. By reviewing 20 years of ROV video, Haddock and his team have spotted many dining encounters in action.

Recently, the MBARI scientists were surprised to see a rarely-spotted species of large octopus carrying around an egg-yolk jelly, which—true to its name—looks like a partially-cooked egg. With the help of archived footage and a collaborator who found gelatinous organisms in the stomachs of five octopus specimens, they became pretty confident about this predator-prey relationship in the food web.

It turns out scientists aren’t the only ones trying to catch jellies.

—

Carolyn M. Wilke is a Ph.D. student at Northwestern University studying environmental engineering. She was a 2017 AAAS Mass Media Fellow at The Sacramento Bee. Find her online at www.carolynmwilke.com and @CarolynMWilke.