How to Defend Science in a Post-Truth World

Susan Desmond-Hellmann, CEO of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, called on scientists and journalists to rise in defense of science. Photo: Nicoletta Lanese

SAN FRANCISCO—Twenty years ago, Susan Desmond-Hellmann was giddy to share Herceptin, the breakthrough breast cancer treatment, with the world. Not once did she worry if the world would believe her.

Were Desmond-Hellmann to introduce Herceptin today, she would confront the challenges of conducting and reporting science in a post-truth world.

“The scientific method is all about humility—all about questioning what we believe is true today,” she said on 27 October at the World Conference of Science Journalists 2017. “The biggest threat to all of us is that the normal, healthy skepticism we all should have for science quickly turns into denialism.”

As a practicing oncologist, clinical scientist and current CEO of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Desmond-Hellmann has witnessed public trust in science dwindle over the past 40 years. She offered guidance on reestablishing credibility in her talk, “In Defense of Science,” the fifth annual Patrusky Lecture from the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing.

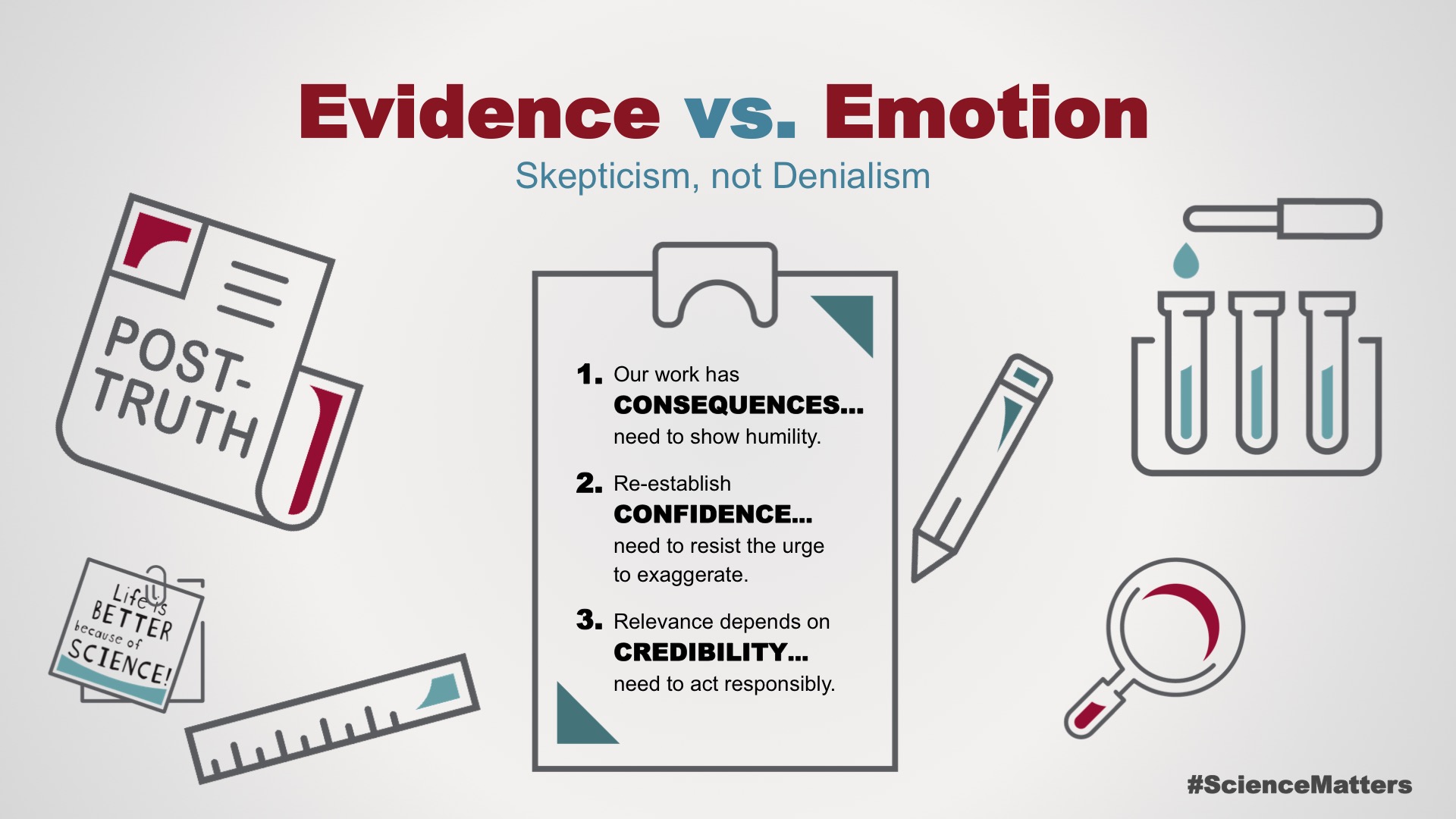

A slide from Susan Desmond-Hellmann’s talk depicts how to establish credibility in a post-truth world. Courtesy of Susan Desmond-Hellmann.

For their work to have impact, scientists and journalists must earn and maintain the public’s respect. Desmond-Hellmann told her audience to remember three C’s: consequences, confidence, and credibility.

Scientists must demonstrate they understand the consequences of their work.

Desmond-Hellmann referred to the development of CRISPR technology, which enables scientists to rapidly edit DNA. If used in embryos, CRISPR could affect generations of people. Jennifer Doudna of UC Berkeley, co-inventor of the gene-editing tool, enhanced her credibility by broadcasting these potential consequences and letting them bear on her decision-making.

Confidence in scientists is undermined by fraud, conflicts of interest and exaggerated experimental results.

Desmond-Hellmann pressed the importance of being forthright about every aspect of the scientific process, including finding negative results. “If the answer is ‘no’ in your trial, say the answer is ‘no,’” she said.

Scientists bolster their credibility by engaging with their communities.

“Credibility doesn’t just rely on telling the truth—that’s a pretty low bar,” said Desmond-Hellmann. “Credibility relies on understanding your audience.” Scientists and journalists alike must understand the needs, challenges, hopes and dreams of the public and use that knowledge to make their work relevant and accessible.

Desmond-Hellmann offered advice on how to engage the public. Avoid jargon and a dweeby professor stance, she said. When your cousin says climate change is a hoax, ask him why he believes that—and listen. Offer your perspective, acknowledge that you’re using the best information available, but note that it could be amended in time. That’s how science works.

You can vaccinate people against denialism.

As a lover of vaccines, Desmond-Hellmann also advised scientists and journalists to use inoculation theory. “Inoculation” means “vaccination,” and inoculation theory says you can vaccinate people against denialism by warning them of tactics that promote it. Her homework for science journalists is to call out denialism tactics and help the world know what to believe.

Casey Rentz and Wayne Himelsein have been doing their homework for the past decade. In a break-out discussion after Desmond-Hellmann’s talk, they described their efforts to popularize science. They organized museum events, held community picnics outside conferences and launched a website where student projects can live on past the science fair.

“The effect was palpable. Everyone was excited about science,” said Rentz.

Despite some successes, Rentz and Himelsein fought pushback from day one—often from the scientific community itself. Without support, they were forced to put their operation on hold.

"All of us who care about funding in science need to have a louder and stronger voice for social and behavioral science to understand denialism."

Institutions were wary of taking a risk on them, Himelsein said, because there is little direct evidence demonstrating the power of communication. Potential supporters wanted hard evidence that the team’s work would effect change.

In response, Desmond-Hellmann called attention to the recent “explosion” of studies about behavioral change. She predicted these studies will help convince data-driven scientists that good communication has tangible effects.

“I would make a plea that all of us who care about funding in science need to have a louder and stronger voice for social and behavioral science to understand denialism—to understand fears of science and advances,” she said.

—

Nicoletta Lanese is a freelancer and science communication student at UC Santa Cruz, as well as a lover of brains, dance and hot caffeinated beverages. Check out her portfolio at nicolettalanese.com and follow her on Twitter @NicolettaML.