How “Decolonizing” Science Can Make It Better

We asked the WCSJ 2017 student journalism travel fellows to translate this phrase into their native languages. Here are some of the results. Image by Liz Kimbrough.

SAN FRANCISCO—When South African student journalist Sibusiso Biyela sat down to write about the launch of the MeerKAT telescope in both English and Zulu, he thought it would be simple. The English version rolled out smoothly. But when he began to translate into Zulu, his native language, he found he would have to tell another story altogether.

“I did not realize that science is different in different languages,” said Biyela. “My mother language seemed inadequate as a language of science—at least, that is what I was told as a child in South Africa.”

With language comes culture, and with culture comes a distinct lens of perspectives through which we view the world. South African freelance journalist Mandi Smallhorne, organizer of the World Conference of Science Journalists 2017 panel discussion “Decolonizing Science” on 27 October, said that “science itself was not in question, but rather where science sits in society, policy, awareness, and education.”

"What does it mean to decolonize science? Is science colonizable?"

“You know the moment one starts to see one’s own privilege?” asked Smallhorne. “This is what I call becoming aware of the wallpaper of your life. I wanted us to see that, not in the science itself, but in the story of science—in how science is told.”

Understanding decolonization

The term “decolonization” has made its way into the mainstream lexicon, from the United Nations’ quite literal definition of a nation gaining independence from colonial rule and the idea of returning land to native people, to the more abstract concepts of decolonizing the mind—and, yes, decolonizing science (one researcher has created a reading list on the topic). However, some of the attendees, and even the panelists, admitted that the subject can be difficult to understand.

“I was really confused by the subject of today’s session,” said panelist Javier Cruz-Mena, a science communicator in Mexico. “What does it mean to decolonize science? Is science colonizable? Can science be made a colony? Or is science an instrument of colonization?”

“The real culprit,” said Cruz-Mena, “may not be science as I understand it, but scientific policy and policy in general. This comes in the form of setting [the] research agenda, funding policies [and] communication strategies, which will include the management of peer-reviewed journals as well as the work of us as science journalists.”

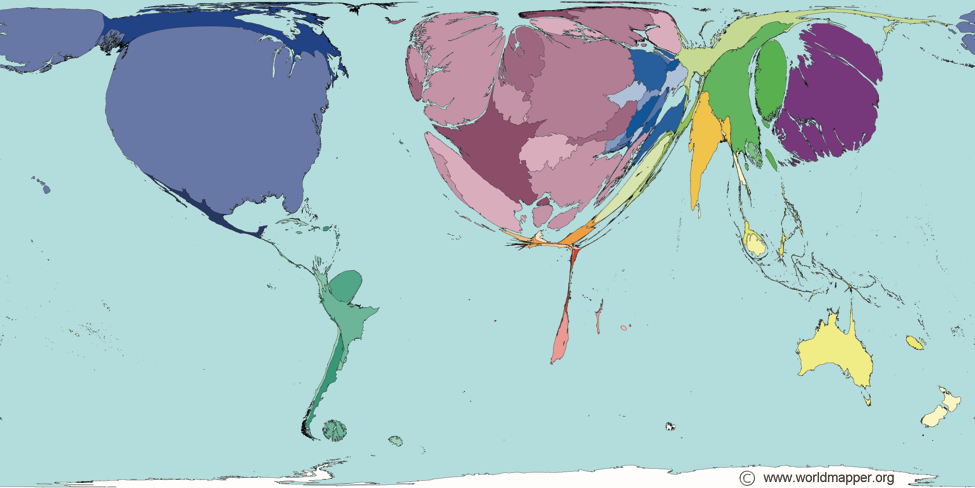

Territory size shows the proportion of all scientific papers published in 2001 written by authors living there. © Copyright Worldmapper.org / Sasi Group (University of Sheffield) and Mark Newman (University of Michigan).

So, how do we move forward? And what role do journalists play in the decolonization of science culture? A few suggestions emerged, such as simply being aware of the issue and the cultural and historical context from which science has emerged. Panelist Padma Tata Venkata, a freelance journalist, spoke about India’s contributions to STEM fields and discussed issues surrounding the exploitation of traditional knowledge.

Nolwazi Mkhwanazi, a medical anthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, addressed “the trouble with a single story.” She cited the case study of a medical male circumcision campaign in Swaziland aimed at curbing the spread of HIV. The campaign failed because the scientists did not consult with or take into account the perspective of the locals—those who were to be circumcised.

The panelists stressed the importance of fostering international collaborations, as well as listening to and interviewing diverse sources such as social scientists and indigenous people. They also recognized the deficiency of publications and science writing in many parts of the world as a core issue.

“I can say with certainty that the lack of writing about science in African languages is a problem,” said Biyela. “But I see decolonizing science not in a negative sense, like you are trying to remove something.” Science, he said, “could be better… if you knew how these other underrepresented people think about the universe. Perhaps the problems the world is facing would be better solved if you consider those other solutions or ways of thinking instead of belittling them.”

In short, said Biyela, “We need to make all languages the language of science.”

—

Liz Kimbrough is a graduate student at Tulane University researching endophytes—the microbes that live inside of plants. When she is not pipetting clear liquids into tubes, Liz has a passion for telling the stories of science—especially the tiny ones here on Earth. See Liz’s work at www.ripplewriter.com or follow her on Twitter @lizkimbrough_