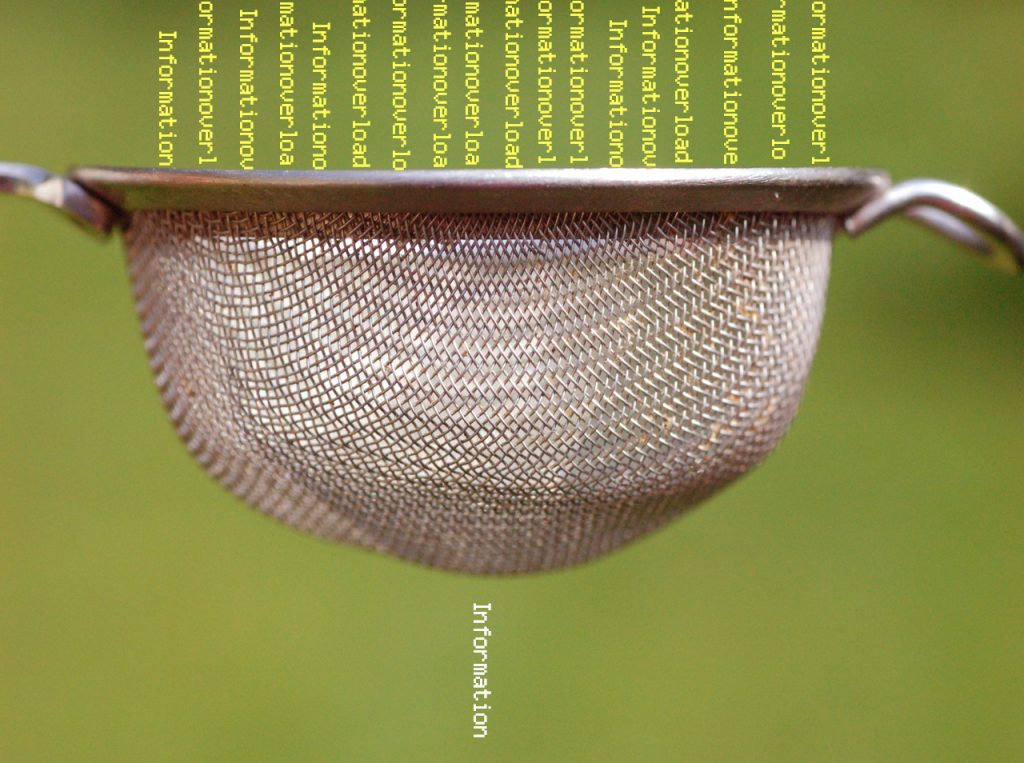

Medical Journal Overload: Databases Help Reporters Mine Healthcare Studies

Illustration: Marina Noordegraaf / Flickr

By Kimber Price

SAN FRANCISCO—In any given field of biomedicine, researchers publish thousands of journal articles each year. How can a healthcare journalist keep up? She can’t.

But given the most comprehensive databases and the most malleable search tools, any journalist can home in on the information most relevant to their needs. And for the icing on the cake: Anyone can use these databases easily, and they’re free.

Those were the take-home messages from two experts on 26 October at the World Conference of Science Journalists 2017. Attendees of a session titled “Tapping Databases for Scientific Evidence on Health” got insider tips to help them search more efficiently for healthcare research information.

Panelists Anurag Acharya, co-creator of Google Scholar, and Robert Logan, communication scientist at the U.S. National Library of Medicine, presented overviews of their databases and step-by-step tutorials on the most efficient ways to navigate each tool.

The world’s largest medical library

The goal of the National Library of Medicine is not to generate research, said Logan, but to “collect and disseminate the world’s health information.” It is the world’s largest medical library and the primary resource for healthcare providers.

Within its oversight are the search engine and repository PubMed.gov, the database ClinicalTrials.gov, and the consumer healthcare information site MedlinePlus.gov. All information provided on the NLM sites is collected and presented in an evidence-based, commercial-free manner, Logan noted.

As a demonstration, Logan led the audience through the steps a journalist might take after seeing an intriguing press release on an archive such as EurekAlert!. His example described a new cancer therapy, so Logan first went to ClinicalTrials to show reporters how to find ongoing and completed trials involving that particular therapy. One completed trial indexed a previous journal article in Pubmed. Clicking on that link, Logan showed how many relevant articles a reporter could access through that portal, including informative review articles.

Another key resource is MedlinePlus, where journalists can find comprehensive general information sheets by searching for any broad or specific disease.

All areas of research in every language

Google Scholar is the largest scholarly search engine, said Acharya, who led the indexing group at Google before helping to create the academic repository. It includes all areas of research in every language. Google Scholar contains journal articles, conference proceedings, books, patents, theses, dissertations and case law.

“Where I grew up in India, the closest library was three hours away.”

The project was intended to be the focus of Acharya’s sabbatical nearly 15 years ago, but it became his primary focus. His motivation for Google Scholar, he said, originated in geography: “Where I grew up in India, the closest library was three hours away.”

The limitations of other scholarly search engines compels Acharya to further the reach of Google Scholar. He is committed to this goal: All research should be available to everyone who might find it useful, regardless of time, place, language or perceived importance.

The platform keeps evolving to serve four primary purposes, Acharya said: to keep up with a familiar subject; to investigate an unfamiliar subject; to find an expert in any given field; and to research case law.

Beyond the paywall

Journalists can set Google Scholar’s search tools as broadly or as specifically as needed, and the engineers frequently roll out new tricks and shortcuts. For instance, journal articles now link to scientist profiles, creating a way to follow researchers and their work.

The databases have one drawback in common: the unavailability of many full-text articles. With embargoes and paid access set up by many journals, there is a limit to what free databases like PubMed and Google Scholar can provide.

But the speakers felt even that may soon change. The future of disseminating scientific research—for both scientists and journalists—centers on transparency.

—

Kimber Price has a Ph.D. in neuroscience and has studied addiction on the clinical and pre-clinical level. She is currently a student in the Science Communication Program at UC Santa Cruz. Reach Kimber at kilprice@ucsc.edu and follow her on Twitter @lowcountrypearl.